The Evolution of Tamil Dowries: From Financial Security to Social Exploitation

- What You Missed In Tamil Class

- Dec 11, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 14, 2025

Explore how Tamils went from indigenous dowry traditions to a socially exploitive system

Weddings mark a transitional phase in one’s life, a new chapter in which one begins their own family.

In ancient Tamil society, this transition was often supported through an inheritance dowry: a voluntary transfer of wealth from parents to daughters at the time of marriage. This could include furniture, gold, jewellery, land, or even a house, and its purpose was to provide financial security and help establish the new household.

Alongside this early inheritance, Sangam literature and folk songs also point to the practice of bridewealth, a practice in which the groom gives gifts such as land, gold, or valuables directly to the bride, and sometimes to her family. When given to the family, these gifts could function as compensation for the loss of her labour; when given to the bride herself, they served as an additional layer of economic security.

Interestingly, these concepts of dowry* and bridewealth were not unique to ancient Tamil society. Across the world and throughout various time periods, similar practices existed.

Take ancient civilizations such as Sumeria and Babylonia. Similar to ancient Tamil societies, both inheritance dowry and bridewealth were given to provide financial security for the bride. Should the groom die or divorce her, the bride was entitled to retain not only her inheritance dowry but also the bridewealth given by the groom.

Across cultures, versions of dowry and bridewealth were used as security for the bride, a starting point for the couple, or as an early inheritance.

Sounds somewhat logical, right?

Unfortunately, the practice of dowries has changed significantly today among Tamil society, now causing immense social and financial pressure for families.

The Shift to Groom-Oriented Dowries

In the 19th century, a shift occurred in which dowries became groom-oriented, meaning dowries were paid by the bride’s family to the groom or his family. This modern dowry practice often included demands far beyond the financial capacity of the bride’s family.

This groom-oriented dowry system is said to have originated in North India. Even there, it was not universal and was reportedly practiced primarily among upper-class groups.

Scholars suggest that dowries in South Asia spread across all social, religious, and economic groups around the 1950s. Botticini and Siow (2003) state that this modern dowry practice first reached the Brahmin community in Madras in the 1930s.

But why? What caused such a shift?

Scholars broadly conclude that social, economic, and property laws played a major role in the emergence and spread of modern dowry practices.

As education, urban employment, and cash incomes became markers of stability, families increasingly competed for a small pool of educated grooms. In this environment, dowry became a means to secure a match and improve one’s social, economic, or even protective standing.

Srinivas (1964) writes that harsh economic realities gave rise to a growing desire among some groom’s families to accumulate wealth at the expense of the bride’s family.

As this new form of dowry treated marriage as an opportunity to acquire wealth and status for the groom's side, the bride was often excluded or treated poorly.

Through folk songs explored by Dr. Ramaswamy, we see that even when bridewealth was given, it did not guarantee respect or protection. One song recounts the story of a father-in-law who was upset after giving bridewealth in exchange for marriage. He was hoping to gain control of the bride’s inherited property, only to discover that her father was too poor to leave her anything.

Women who were once financially protected through these marriage-related transfers of wealth lost control and access to what was gifted by their families. Dowries and land were often seized by in-laws when husbands died. The practice of parents gifting land to daughters also declined, leaving women in vulnerable economic conditions (Ramaswamy 1992).

The purpose of modern dowries thus became clear: to function as a tool for social status and wealth accumulation for the groom’s family, taking advantage of the vulnerability of the bride’s family.

That said, not all marriages or regions operated in the same way. In some cases, brides retained property rights over their inheritance, while in others these rights were merged with or entirely lost to the groom’s family.

Scholars note that during the colonial period, dowry-based marriages became the primary legally recognized form of marriage. However, in parts of South and Central India, where cross-cousin marriage and marriage within family networks were common, this shift was unevenly absorbed. In these contexts, wealth tended to circulate within extended families rather than being transferred outward, which reduced the incentive for large groom-demanded dowries (Botticini and Siow 2003).

These outcomes and effects of modern dowries varied by family, region, and country. However, there is no recorded instance of an entire Tamil region or country successfully rejecting groom-oriented dowry practices, despite legal efforts to do so.

Laws

India enacted the Dowry Prohibition Act in 1961, making it illegal for either the bride’s or groom’s side to demand dowry. The Act was later expanded to include laws addressing dowry-related violence, an issue that remains highly relevant in India today. While demanding dowry was criminalized, inheritance given voluntarily to daughters by their families remains legal.

Under the Tamil Eelam Penal Code and Tamil Eelam Civil Code enacted in 1994, dowries were also banned. These laws were enforced during the late 1990s and early 2000s when the LTTE had control over the Tamil homeland. Within this legal framework, inheritance given to daughters were permitted, while dowry demands by the groom’s family were prohibited.

The inheritance dowry practice in Eelam is notable for its connection to matrilineal inheritance systems.

Matrilineal inheritance refers to a system in which ancestral property and lineage are traced through the mother’s line, meaning that daughters and sisters’ children hold ultimate inheritance rights, even though land and resources may be cultivated or managed by men during their lifetimes.

Based on decades of fieldwork in Batticaloa, eastern Eelam, beginning in the 1970s, McGilvray (2011) explains that inheritance to daughters at the time of marriage was almost universal. This inheritance could include a house, paddy fields, household furniture, vehicles, clothing, jewellery, and cash. Legal title to houses and land was typically registered in the daughter’s name or later shared with the son-in-law once his reliability was established.

Here, dowry functioned not as a payment to the groom’s family, but as security for the bride and a transfer of ancestral wealth.

McGilvray (2011) also notes: “Typically, it is the mother’s dowry house that becomes her eldest daughter’s dowry house, unless there is a demand by the prospective groom for something newer or fancier.” This raises questions about whether such demands were common or a byproduct of the modern dowry system.

It’s important to note, the diverse indigenous inheritance traditions across the island were not merely customs, but customary laws.

Prior to colonial rule, Tamil communities had their own legal systems governing inheritance, property, and marriage, varying by region and community. Under colonial rule, courts stopped recognizing these customary laws, families were pressured into selling land, and colonial land policies altered patterns of land ownership. These shifts played a significant role in paving the modern dowry practices that were later banned under LTTE governance.

The Tamil Eelam Civil Code introduced reforms such as granting women the right to sell property without spousal consent, among other laws recognizing women as legally free and equal individuals. However, these changes were short-lived due to the ongoing conflict.

Modern Times

Despite laws and banning attempts, dowries continue to be demanded. Social pressure within Tamil communities has normalized the practice to such an extent that even when groom’s families claim they do not want a dowry, brides’ families often feel compelled to provide one, frequently beyond their means, as a marker of social status (Srinivasan 2005).

As one senior lecturer from the Sociology Department at the University of Jaffna shares:

“In the North of Sri Lanka, the dowry system is very strong. During the war, this situation was somewhat moderated, but now dowry discussions have resurfaced. Most current divorces are due to dowry issues. Some ask for dowries not out of need but to display their status” (Sudusingha).

In a post-war Eelam, we see a mixture of traditional inheritance dowry practices heavily influenced by groom-side demands, alongside fully modern dowry systems. Factors such as the loss of men through conflict, disappearance, and migration, combined with post-war militarization in Tamil regions, have coincided with rising dowry pressures, as explored in this article shared by The Tamil Guardian.

Many women have left marriages or ended their lives due to dowry-related pressure and abuse, which often continues after marriage (Srinivas 1964). Young women across South Asia have been burned, murdered, or subjected to domestic violence by husbands and in-laws for their families’ refusal to meet additional dowry demands. Kaur and Byard (2020) report that approximately 21 women die daily in India due to dowry harassment.

One may ask why such a cycle continues. Accounts from articles and shared narratives suggest that, in some cases, families demand dowries in order to pay for their own daughters’ dowries, perpetuating the system across generations.

This is not to say that all members of the Tamil community participate in these practices. Nor is this a universal tradition, though it remains a common and deeply entrenched one.

Assessing “True” Tradition

I often hear practices in the Tamil community defended in the name of tradition, but what truly constitutes tradition? Is it what emerged in the 19th century, or what existed before?

The practice of inheritance from the bride’s family, or bridewealth in which the groom gifts the bride financial security, is widely suggested to be the indigenous Tamil tradition.

There are abundant references in Sangam literature and folk songs to bridewealth, but none to the modern practice in which the bride’s family gifts wealth to the groom and his family (Ramaswamy 1992; Ramaswamy 1993).

Perhaps instead of using “tradition” as a shield for inhumane behaviour and exploitation, we owe it to ourselves to think deeply with our history before choosing what to preserve, or reject.

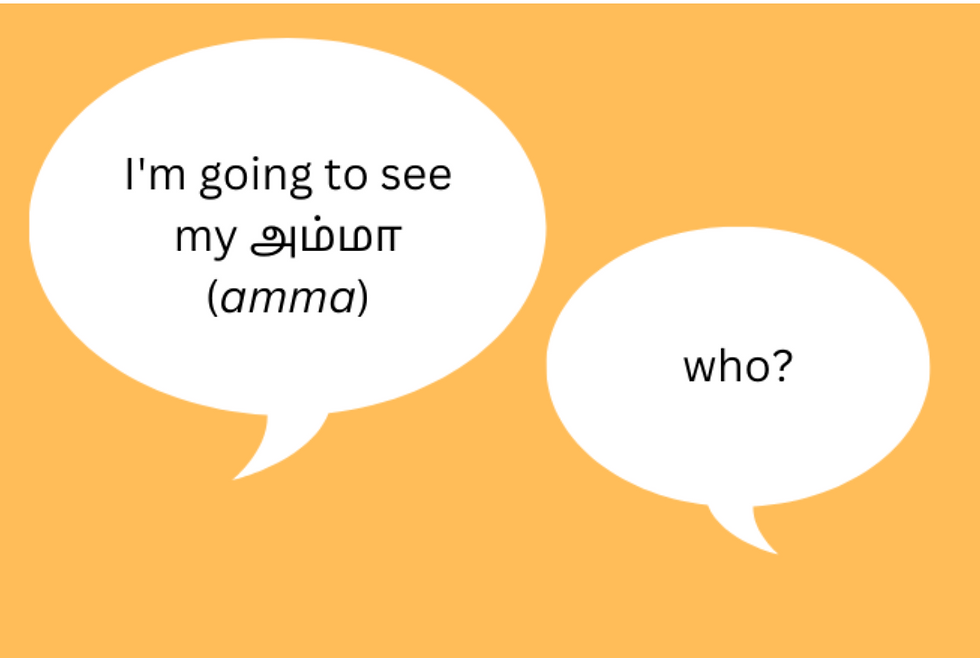

Note: In some academic papers and articles, the term dowry is used specifically to describe what I refer to here as the modern or groom-oriented dowry. In other sources, the same term is used more broadly to include both inheritance-based transfers and modern practices.

Sources

Becker, Gary S. “A Theory of Marriage.” Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital, edited by Theodore W. Schultz, University of Chicago Press, 1974, pp. 299–351. National Bureau of Economic Research

Botticini, Maristella, and Aloysius Siow. “Why Dowries?” American Economic Review, vol. 93, 2003, pp. 1385–1398

Kaur, Navpreet, and Roger W. Byard. “Bride Burning: A Unique and Ongoing Form of Gender-Based Violence.” Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, vol. 75, 2020, article 102035

McGilvray, Dennis B. “Dowry in Batticaloa: The Historical Transformation of a Matrilineal Property System.” The Anthropologist and the Native: Essays for Gananath Obeyesekere, edited by H. L. Seneviratne, Anthem Press, 2011, pp. 137–160.

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Women and Farm Work in Tamil Folk Songs.” Social Scientist, vol. 21, no. 9/11, Sept.–Oct. 1993, pp. 113–129. JSTOR

Ramaswamy, Vijaya. “Women, Dowry and Property in Tamil Folk Songs.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 53, 1992, pp. 181–186. JSTOR

Soni, Suparna. “Institution of Dowry in India: A Theoretical Inquiry.” Societies Without Borders, vol. 14, no. 1, 2020

Srinivas, Mysore Narasimhachar. Social Change in Modern India. University of California Press, 1964.

Srinivasan, Sharada. “Daughters or Dowries? The Changing Nature of Dowry Practice in South India.” World Development, vol. 33, 2005, pp. 593–615.

Sudusingha, Sandarasi. “Dowry: The Serpent Sustained by Tradition.” Mawrata News, 6 July 2024.

Comments